Objave

Concept of love and freedom

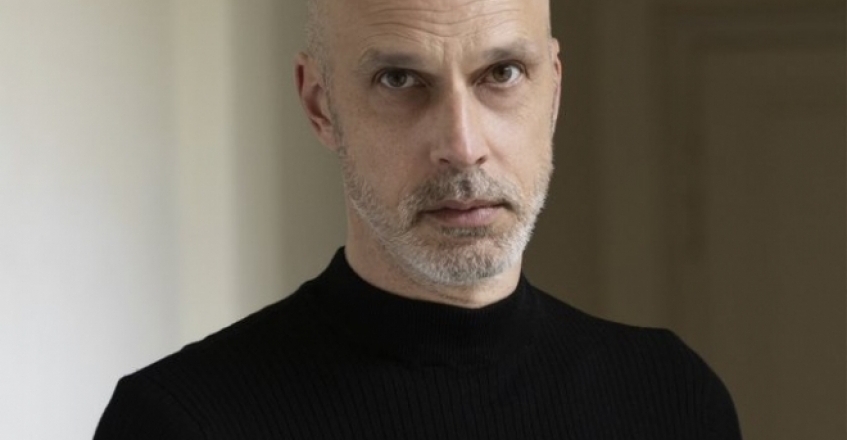

Interview with Sebastian Meise, director of the film GREAT FREEDOM

Your film is about the real events in Germany after the Second World War and the shameful article of the law that spied on, persecuted and imprisoned men caught in homosexual relations. Are the characters the fruit of your imagination or have you built them on existing people as well?

The characters in our film are fictional, but their stories are based on the stories of people we met during our research. These men were themselves convicted and imprisoned on the basis of Paragraph 175. Hans, our main protagonist, personifies the fate of the many people who ended up in prison again and again, whose livelihoods and relationships were destroyed, and whose stories vanished in the files of bureaucracy.

The main actors are brilliantly chosen. They entered the film with all their acting beings, not just with technique and knowledge. Their mutual interaction makes an immeasurable contribution to the film’s persuasiveness. How did you decide on Franz Rogowski and Georg Friedrich and what was it like working with them?

While we were working on the script I already started to think about the cast. Franz and Georg were immediately the only actors I could imagine in these roles and I know now I couldn’t have made this film without them. One of the main tasks in staging the film was to capture the chemistry that exists between them as actors, but also as human beings. This in the end has become the heart of the film. Working with them was very intense. Both invest an incredible amount in what they do, are extremely precise, and demand the same of the director. I'm very happy that I had the opportunity to learn from them.

You have paid special attention to music that often sounds like Hans's inner monologue. There is no orchestration in the sad prison environment, only the melancholic, longing trumpet of Nils Petter Molvær. When Hans enters Great Freedom, fierce free jazz is heard. In a scene in which Hans sees as if in a dream scenes that have been forbidden for most of his life, a love chanson is played. What follows is a return to reality and free jazz again. How did you choose the music and did you do it while writing the script or when you edited the film?

I already thought of Peter Brötzmann while writing the script, we wrote the scene in the club for him, Nils Petter Molvær and the chanson by Mouloudji came during editing. I always saw this film in between two genres, the prison drama and the love story. There is the rawness and ugliness of law enforcement, and within this frame we have our characters trying to give their lives a deeper meaning, which they only manage to find in the trust and tenderness between two human beings. The less music you use, the more you will notice if it is missing. The gaps should therefore stand for the prison drama with all its bareness and severity. But what, in order to keep reminding ourselves that we are actually watching a love story here, should be broken regularly with the devoted solo trumpet by Nils Petter Molvær. Peter Brötzmann's Free Jazz stands for the deconstruction, like a cathartic discharge. And of course a love song should not be missing at the end.

There is a question that went through my head long after watching the movie. What makes people so heartless and cruel to people weaker and different from themselves? What do you think?

These are two very difficult questions. We faced the first one over and over again while we were working on the film, and I believe that the motives for oppression are not always the same. In our story there is the Nazi guard whose actions are predominantly marked by hatred and contempt. Then there is the guard from the 1950s. He actually believes in the principle of discipline and order and that people can be reformed with severe punishment. He has moments in which his humanity comes to the fore, but which he has to suppress, otherwise he would have to destroy everything he believes in. He can't help it. Then there is the guard from the 1960s. He has no principles; he is part of a system and does his job because someone has to do it. For him, however, the rules do have a certain amount of leeway.

What is more necessary in life, freedom or love?

To be perfectly honest, the concepts of both freedom and love are too broad for me to grasp. In our story they are closely related and I can say with certainty that it is completely a mystery to me how a society can criminalize love. Paragraph 175 wasn’t just inhuman, but also against constitution. For decades the state refused to accept that it had infringed upon people’s human rights – the rights it should have been protecting. And in many cases gay people encounter the same attitude to this very day. Naturally people can eventually become exhausted by this constant battle for acceptance, and then they may prefer to create parallel worlds where they can find the freedom they have always been looking for. In that way the concept of freedom, and also of love, becomes a very personal one. Our main protagonist Hans finds love in prison, of all places. And with a convicted murderer, of all people. In our free democracies it may seem that the battle for equality no longer needs to be fought. But if you bear in mind that the history of culture is full of cyclic repetition, you become aware how fragile this achievement is. But in my view, the longing for freedom and love can’t be suffocated.

Marinela Domančić